+

Read More

A Palimpsest Planned

by Will Self

Published in The World Of Interiors April 2014

‘The house is a living skeuomorph: like the little envelope icon on an email programme, it draws the mind back to a previous era and its technologies, and privileges these as exemplary of other modes of existence: closer to the earth, more genuinely relaxed.’

I’ve known Alastair Hendy, the food writer and photographer, for almost twenty years, and have long been captivated by the particular skills he brings to the business of quotidian existence: every meal, no matter how simple or thrown-together, is an aesthetic creation (as well as tasting fabulous); the industrial-conversion apartment in London’s Shoreditch he shares with his partner, John, is a triumphant merging of the functional and the comfortable. The couple bought a section of the building – a former print works, built in 1912 – in the mid-1990s. Alastair told me: ‘It was a shell space, there weren’t even any dividing walls, and I had to cut out a section of the floor to put in the staircase down to the basement.’ Because of peculiarities of the finance, Alastair was forced to do the conversion in seven very quick months; yet the results remain just as fresh and clean today. Alastair says with typical self-deprecation: ‘Let’s face it, once you’ve done a house up, that’s it – you never touch it again.’

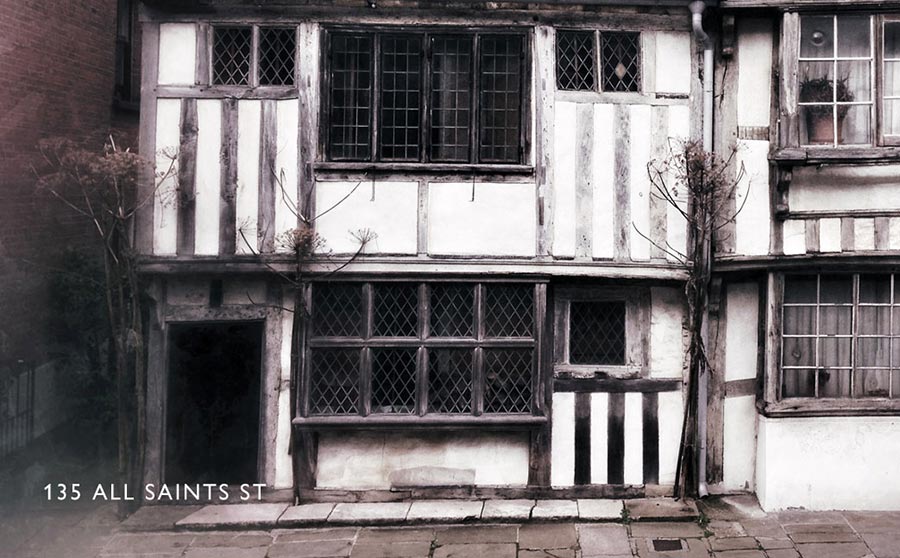

I wonder if he will feel the same way in another 15 years about the astonishing transformation he has wrought on 135 All Saints Street, a Grade ll Listed 16th century merchant’s house in Hastings Old Town. Alastair’s connection with Hastings goes back to his earliest childhood, and the Hendy family have for many years had a cottage at nearby Battle. Wandering about on the seafront, among the characteristic multi-storey fishermen’s huts, and observing the colourful detritus – crab shells and lobster pots – left behind by the only shore-launched fishing fleet still extant on the South Coast, Alastair’s eye strayed inland to where All Saints Street wound uphill, lined with half-timbered houses. ‘But you know,’ Alastair says, ‘Hastings Old Town isn’t typically Tudor – if anything the prevailing architectural style is Georgian. My sense as a child was of this astonishing gallimaufry of different periods: each successive layer of renovation working over what had gone before, like a palimpsest.’

In 2006, long grown to be a man, Alastair’s eye alighted on 135, now integrated into a single structure, but which was originally two houses: the main front one was built around the time of the Spanish Armada in the late 1580s, the older back part was once a complete property as well, and its timber frame may date back as far as the 1400s. The two-bay frontage of the house is deceptively small when viewed from the front. In fact there are four storeys, and following Alastair’s restoration the rear wing is double-height space containing kitchen, dining room and semi-underground cellar. In the paved back yard there’s an outdoor toilet and shower, as well as some rather minatory Giant Caucasian Hogweed.

‘I never had the vision of the house as it now is in mind,’ Alastair says, ‘I just looked over the property – the interior of which had indeed been made as near-contemporary as possible – and this obsession gradually took hold of me.’ It was an obsession that resulted in a highly original vision. There were indeed major structural problems with the house – a long-time lurch to the right that had happened when the adjoining property collapsed – and Alastair now concedes that: ‘Had I realised then what a political and bureaucratic business it would be to restore the house, I might not have taken it on.’ The political business was winning over the conservation officer, and the bureaucracy was the redrawing and resubmission of set after set of plans – a process that in its very constriction mimicked the tight spaces the craftsmen Alastair engaged found themselves working in. But the key word here is ‘restoration’.

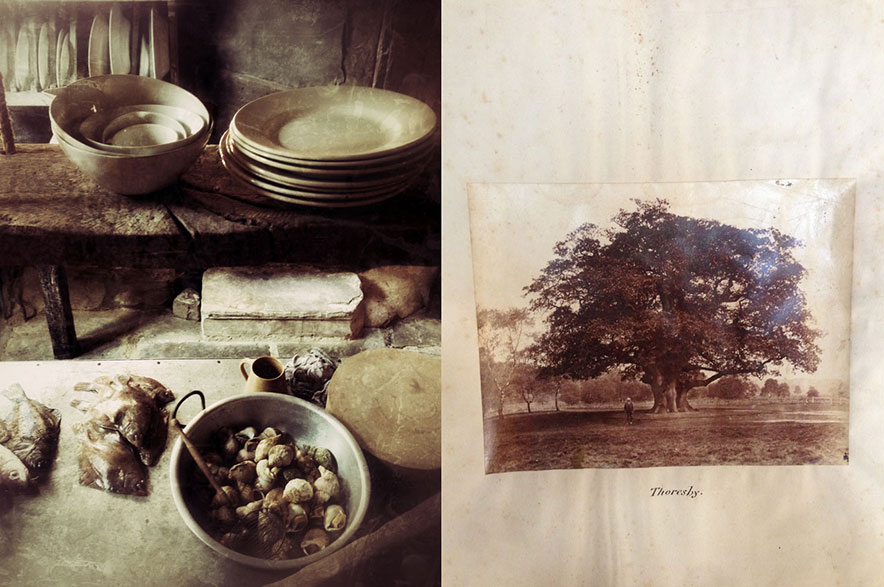

Alastair effectively put himself through a rapid course in 16th century building techniques, so that he could appreciate exactly what was entailed in stripping away the layers until he was left with the original timbers that were still sound. New oak beams were then cut and fashioned by hand using an adze; horsehair and lime plaster was applied to the walls; floorboards and doors were built using groyne oak – reclaimed from local beaches. Alastair is measured in his praise for the craftsmen who worked on the house: ‘Good craftsmen are,’ he says, ‘difficult, like all creative people – but they want to be proud of what they do, as well earn their money.’ He singles out Nick Wheeler, a local carpenter and master of many trades for particular attention: ‘Nick is brilliant with his hands, he did a lot of the detailing and the pipe work – he even cut out a shower rosette from an old copper water tank.’

And then there was the devilish detail: lead and copper nails used around sink units and to line the bath, and then trawling architectural salvage yards, antique fairs and even Ebay for precisely the fixtures and fittings he wanted. The aim, however, was not to create a simulacrum of the house as it might have been in the 1600s, but something far more interesting, which was to imagine what the Tudor house might be like, if, each successive domestic technology had been introduced without otherwise altering the original fabric. Thus the plumbing belongs to 18th century, the central heating to the 19th, and the electricity to late 19th or early 20th century. The eclectic mixture of furniture styles and periods is also responsive to this vision of organic homely growth: an 18th century settle with its original paint is juxtaposed with rush-backed 19th century Orkney chairs.

Alastair, perhaps being a little pat, describes this form of restoration as ‘Putting back the years the years have taken away,’ but then smiles wryly and concedes that a friend once said: ‘You’re the only man I know who can take a home and turn it into a house.’ This is, I think, unfair comment. The Tudor house, as re-imagined by Alastair, is rather a living skeuomorph: like the little envelope icon on an email programme, it draws the mind back to a previous era and its technologies, and privileges these as exemplary of other modes of existence: closer to the earth, more genuinely relaxed. ‘It’s a winter house, really,’ he tells me ‘what with all these open fireplaces, and the intensely cosy feel to the lighting. The aim is certainly to live here – but family issues have prevented us occupying full time.’ Family issues, and Alastair’s expansionism: not long after he took on the Tudor house he acquired a nearby Georgian shop premises, and this too he has lovingly restored, and transformed into an astonishing shop – Hendy’s Home Stores – and café. This building, like the Tudor house, is a sort of steam-punk creation: an alternative vision of what domestic space might be like if change were an gradual organic process, rather than a permanent revolution of sheetrock, MDF and track lighting.